Equity and Justice: why it matters in UK Government digital services and what we can do about it

Some groups of people benefit more from services than others. Some people are harmed. This must be addressed to truly break down barriers to opportunity for everyone.

This article talks about what we mean by equity and justice in relation to government digital services, why it’s important and suggests 6 things that leaders and decision makers can start doing about it today.

There are unequal outcomes for users of government digital services.

This might be easier to identify when we think about services like health and education. For example, a recent MBRRACE-UK report states that Black women are 3.7 times more likely to die during or in the first year after pregnancy than White women and a study buy the IFS found that more than 70% of children from the richest tenth of families earn five good GCSEs, compared with fewer than 30% in the poorest households.

These differences are also present in digital services. For example, in 2020 a BBC article reported that women with darker skin were more than twice as likely to be told their photos fail UK passport rules when they submit them online than lighter-skinned men. This could prevent darker skin women from getting ID, travelling or getting access to other services.

Some groups of people benefit more from services than others. Some people are harmed. This must be addressed to truly break down barriers to opportunity for everyone.

As we become more reliant on digital services, the importance of keeping equity of outcomes for everyone in mind grows. If we aim to make interacting with government digital services more convenient and time efficient then equity and justice must be part of that too.

Digital helps us scale and reach more people, faster, yet it also can scale inequity and harm through things like poor implementation, biassed algorithms, untested emerging tech inadequate research or simply failure to consider the implications of our choices.

When we speak of outcomes, we are talking about more than just whether users have access to a service, or what their experience of using the service is like. Outcomes include what a user gets out of a service, how it meets their needs or not and how it benefits or harms them.

Examples of unequal outcomes for different groups in UK public digital services

The problem of unequal outcomes and unjust digital services is real and present. Consider these cases:

- A digital identity service can stop someone from applying for benefits if they can’t pass the criteria. The Department for Work and Pensions (DWP) chooses how strong an identity check they require and the digital identity service contains a decision algorithm which decides who passes and who doesn’t. This can have a huge impact on people’s lives, and could even lead to death, such as what happened to Errol Graham.

- To apply for a National Insurance number, people are required to describe themselves as either male or female. This question prevents many trans, non-binary and intersex people from getting a National Insurance number. It fails to acknowledge their identity as valid and can prevent them from working and accessing many other services.

- For people who are not fluent in English the specific terminology used in the register to vote process was a barrier to registration. Senior Oyster cards and bus passes are considered valid forms of ID, but youth ones are not. This prevents whole groups of people from being represented in our democratic processes.

There are many other examples of the ways in which outcomes of digital services are unjust and unequal.

These inequalities are frequently associated with race, sex, gender identity, sexual orientation, age, disability, and other protected characteristics, as well as socio-economic or geographic inequalities, and other forms of vulnerability in society. A study by Truth Consulting, for Barclays Bank found that “age, income level and disability are the most significant demographic factors in creating either total or partial [digital] exclusion.”

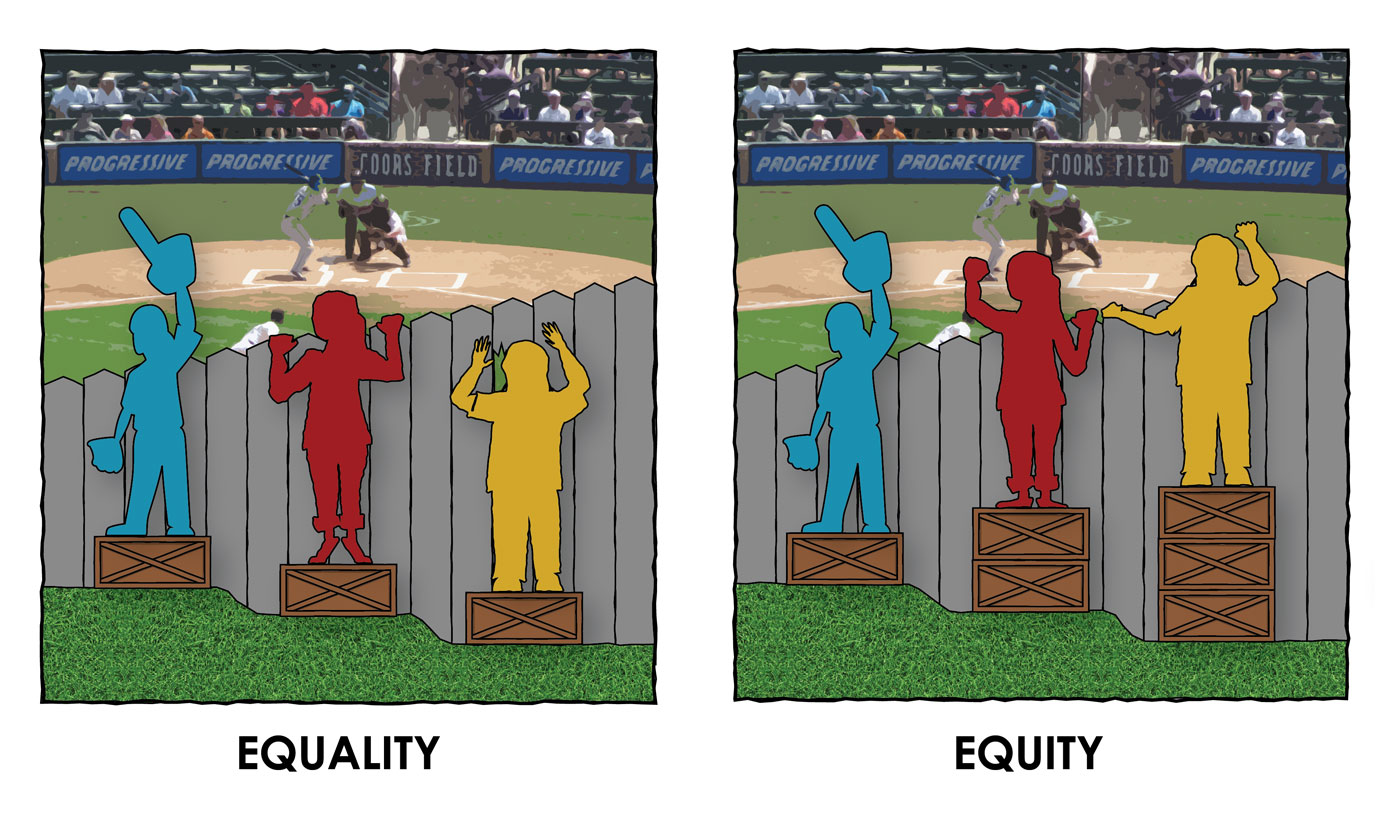

Equity vs equality

Making our services and products just and equitable means making sure everyone gets equal outcomes.

Equality means each individual or group of people is given the same resources or opportunities.

Equity recognizes that each person has different circumstances and allocates the exact resources and opportunities needed to reach an equal outcome.

Milken Institute School of Public Health

As people who make decisions about, create and deliver digital government services and products, it’s in our power to either exacerbate these inequities, or to address them.

The public sector equality duty is part of the Equality Act 2010. It says that we have a duty to advance equality by:

- Removing or minimising disadvantages suffered by people due to their protected characteristics.

- Taking steps to meet the needs of people from protected groups where these are different from the needs of other people.

In order to build an NHS fit for the future, we must consider equity when we design digital services for health. The NHS constitution states that:

“… it has a wider social duty to promote equality through the services it provides and to pay particular attention to groups or sections of society where improvements in health and life expectancy are not keeping pace with the rest of the population.”

How to prioritise equity and justice in decision making

The longer we wait to address these issues, the more we prioritise other concerns, the more harm we do. We need to act now.

To address the inequities in digital services, we need to look at:

- what decisions we make

- how we work and

- what we create

Here are some of the things we can do:

1. Measure the outcomes of services in terms of equity

Make a policy commitment to improving the equity of outcomes for our digital services - identify the main services or groups of people where outcomes are unjust, measure and benchmark those outcomes and make explicit policy commitments and strategic decisions to improve those measurements.

2. Build equity and justice explicitly into our work

Some things that we can add equity and justice to:

- Manifestos

- Policy

- Strategies

- Principles and standards

- Agendas

- Job specifications (particularly senior ones) and objectives

- Tenders and briefs

- Roadmaps

This will help it be present in our tools, methods and everyday practices, and will hold us accountable.

3. Prioritise and fund work on equity and justice

Instead of prioritising work by the number of users, consider prioritising it by the number of users excluded, or by the amount of harm done.

Fund and resource this work explicitly, not as an optional add-on to other streams of work.

Encourage people to explore different ways of working and thinking.

4. Talk about equity and justice whenever we can

Get used to using the language of equity and justice in digital contexts. Educate ourselves and those around us. Ask questions about it all the time:

- Who might be harmed by this?

- What distribution of benefits do we believe is just?

- What values have we built in?

(questions inspired by Design Justice by By Sasha Costanza-Chock)

5. Find, uplift and fund people already working on these issues

There are many. They are probably struggling against the structures around them and as a result are often close to burnt out. Actively support them and they can do so much more.

6. Hire diverse teams

There’s already so much information about this available, including some work we did at the Government digital service on improving equity and measuring the makeup of our teams. There is also a podcast interview between the brilliant Adaobi Ifeachor and myself.

Working towards equity and justice in public digital services isn’t easy. As people who make decisions about these services, we have the power to change them, and we have a responsibility to try.

Further reading

Book: Design Justice by Sasha Constanza-Chock

Book: Race After Technology by Ruha Benjamin

Book: Public and collaborative: exploring the intersection of design, social innovation and public policy by DESIS Network

Article: It’s Time to Define What “Good” Means in Our Industry (14 March 2019) by George Aye

Article: The Hidden Privilege in Design (October 23 2018) by Hareem Mannan

Thanks

Thanks to Alistair Greo, Sonia Turcotte, Kara Kane and Ignacia Orellana for your help in shaping these ideas and getting this article published 💫